Waterloo

From 2007.igem.org

(→Acknowledgements) |

(→Project Details) |

||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

==Project Details== | ==Project Details== | ||

| - | |||

===Inputs=== | ===Inputs=== | ||

Revision as of 21:50, 21 October 2007

University of Waterloo iGEM Team

University of Waterloo iGEM Team Contents |

Our Team

The UW iGEM team is a very interdisciplinary group. Our team members span the three faculties of Science, Mathematics and Engineering and include the programs of Biology, Biomedical Sciences, Computer Science, Bioinformatics, Computer Engineering, Electrical Engineering, Chemical Engineering, and Mathematical Physics at undergraduate and graduate levels. Even our professor advisors are cross-appointed to two other faculties. Our diverse backgrounds bring together a wide range of skills and ideas to the iGEM project. iGEM is giving us the opportunity to apply the skills learned in our lectures and labs to real life applications in molecular biology and biotechnology.

Abstract

Background

Binary Addition

When working in binary, only two digits are used: 0 and 1. Counting therefore proceeds as:

- 1

- 10

- 11

- 100

- 101

- 111

etc.

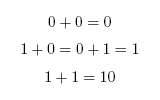

To add two binary numbers, the process is much the same as adding two decimal (ordinary) numbers, except that instead of carrying when two digits add to ten, carrying must be performed when two digits add to two. In other words, 0 + 1 adds to 1, but 1 + 1 adds to 0 with a carry of 1, which gives 10 (just as in decimal 1 + 9 would add to 0 with a carry of 1, to give 10). A complete list of the possibilities is as follows:

Half-Adder vs Full-Adder

Any construct designed to add two numbers will either be a half-adder or a full-adder. A half-adder can only add together two single digits, whereas a full-adder is needed to add two numbers of any length greater than one digit.

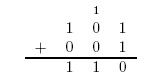

For example, a half-adder could perform the addition 1 + 0 = 1, or 1 + 1 = 10, but it would take a full-adder to be able to perform 1100101 + 100101.

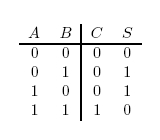

In terms of implementation, a half-adder accepts two inputs (the two digits to be summed) and returns two outputs (the "sum bit" and the "carry bit"). To add 1 + 1, the two inputs would each be 1, the sum bit would be 0, and the carry bit would be 1. A full list of the possibilities is shown in Figure 1.

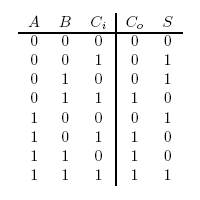

A full-adder is merely a half-adder that accepts an extra input; namely, the carry bit from another full-adder. Each full-adder is responsible for adding one pair of corresponding digits from the two numbers to be added, and it must add to that the carry bit from the previous full-adder. The full-adder will output the resulting sum bit and carry bit, and the process will continue until all the digits have been added. Such a chain of full-adders is called a ripple carry adder. See Figure 2 for a full list of possibilities.

Logic Gates and Implementing an Adder

A logic gate is a device that accepts two binary input(s) (each a 0 or 1) and returns one binary output. A list of relevant logic gates is as follows:

- OR gate

- XOR gate

- AND gate

- NOT gate

For the following explanations, A and B represent statements that can be either true or false.

OR Gate

Consider the statement "A OR B". If either A or B is true, the statement is said to be true. The only time this statement will be false is if both A and B are false. This is the meaning of the OR operation.

An OR gate accepts two binary inputs, where a 1 to represents "true" and a 0 represents "false". The output of the OR gate is also binary, and similarly represents either "true" or "false".

To illustrate,

0 OR 0 = 0

1 OR 0 = 0 OR 1 = 1

1 OR 1 = 1

XOR Gate

XOR is an abbreviation for "exclusive OR". The XOR gate is similar to the OR gate, the only difference being that it will return false if both inputs are true.

For example,

1 XOR 0 = 1

1 XOR 1 = 0

AND gate

The AND gate will return 1 (true) only if both the inputs are 1 (true). Otherwise, it will return a 0.

To illustrate,

0 AND 0 = 0

1 AND 0 = 0 AND 1 = 0

1 AND 1 = 1

NOT gate

The NOT gate accepts one input, and simply switches its value.

NOT 1 = 0

NOT 0 = 1

Using logic gates to make an adder

Given two binary inputs A and B, their sum can be computed by passing these inputs through various logic gates. The process is illustrated in Figures 4 and 5.

DNA as Logic Gates

The crux of our project is the idea of using DNA as logic gates.

Project Details

Inputs

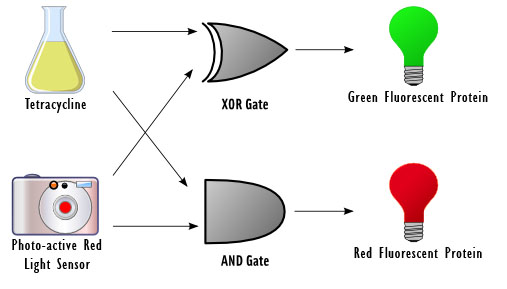

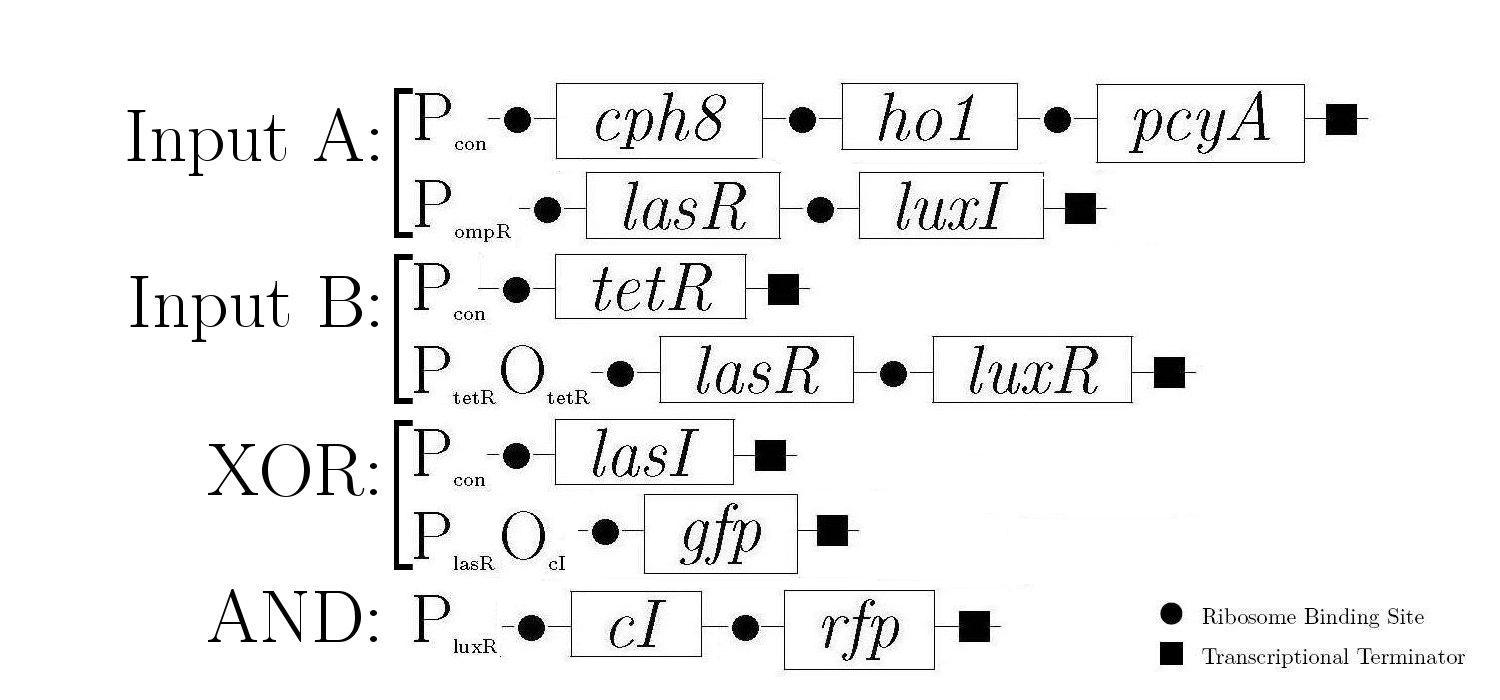

As a half-adder, our cells require two binary inputs. We chose to use the presence or absence of red light as one input, and the presence or absence of the chemical tetracycline as another. For the first input, the presence of red light represents a 0 and the absence represents a 1. For the second input, the absence of tetracycline represents a 0 and the presence represents a 1.

We chose to use light as an input for the reasons that it does not require altering the media, it can be turned on and off rapidly, and it has extremely high resolution and accuracy. The red light will be detected by the previously used Cph1/EnvZ fusion protein ([http://partsregistry.org/Part:BBa_I15010 BBa_I15010]).

Tetracycline

Output

Depending on the result of the calculation, the bacteria will produce either red fluorescent protein (rfp), green fluorescent protein (gfp), or neither. The possible outcomes are as follows:

0+0 ==> nothing

0+1 ==> gfp

1+0 ==> gfp

1+1 ==> rfp

Schematic Diagram

Gene Diagram

Testing/Results

Mathematical Model

Measurements

Extensions

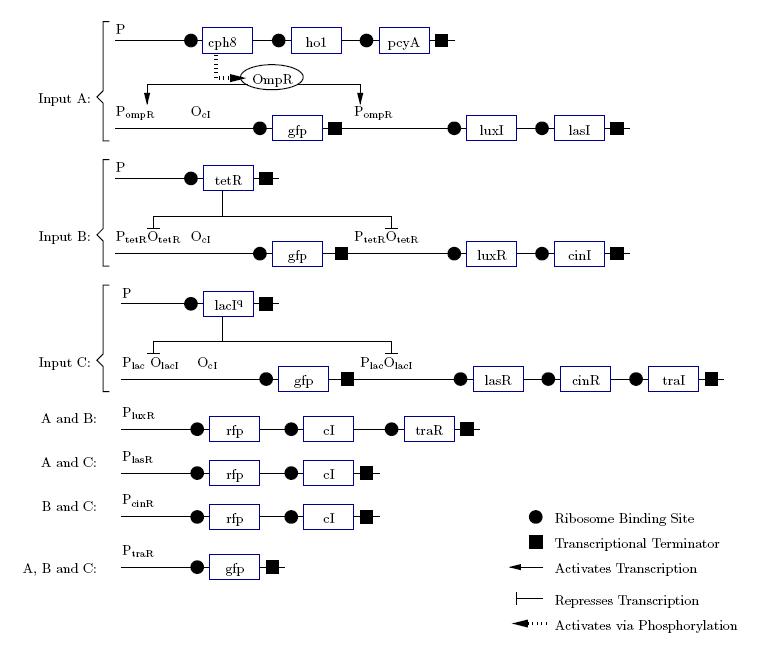

Full Adder

As a future project, we would like to extend our half-adder to a full-adder, which would be much more useful as it would give us the ability to add numbers of more than one digit. A gene design that makes use of some of the half-adder components can be seen below.

==Acknowledgements== (Sponsor logos) The UW-iGEM team would like to thank the following organizations and individuals for their contributions:

WEEF

MEF

WatSEF

[http://www.science.uwaterloo.ca/fsf/index.html Faculty of Science Foundation]

[http://www.science.uwaterloo.ca/fsf/index.html Faculty of Science Foundation]

SFF

Dr. Trevor Charles