Thanks to our Sponsors:

|

The original plan for our project was to model the dynamics of the spread of an epidemic within a population. We hoped to make a multi-scale model of epidemic spread and test it in a model population...

Using modern air travel, it is possible to travel around the world, often several times, within the time it takes for a viral infection to show symptoms. This complicates the early detection of epidemics, making it even more important to predict whether an infection will become an epidemic as early as possible. If an infection is "treated" on a worldwide scale early enough, an epidemic could be prevented. Since transportation and communications technology has changed so rapidly in recent years, research needs to be done to find new ways of combating epidemics.

With this problem in mind, we set out to revolutionize an approach to modeling epidemics. We wanted our model to be testable, which is vital to verify its accuracy. Therefore, we would not be reliant on historical records like many epidemiological approaches do. These records can be imprecise or inaccurate, and we knew we could get more accurate data from our testable system. We also wanted to make more use of stochastic modeling, using equations that take random variations into account. The event of an infection either becoming an epidemic or dying out in its early stages is a highly random event influenced greatly by small fluctuations among individuals.

A Multi-scale Model

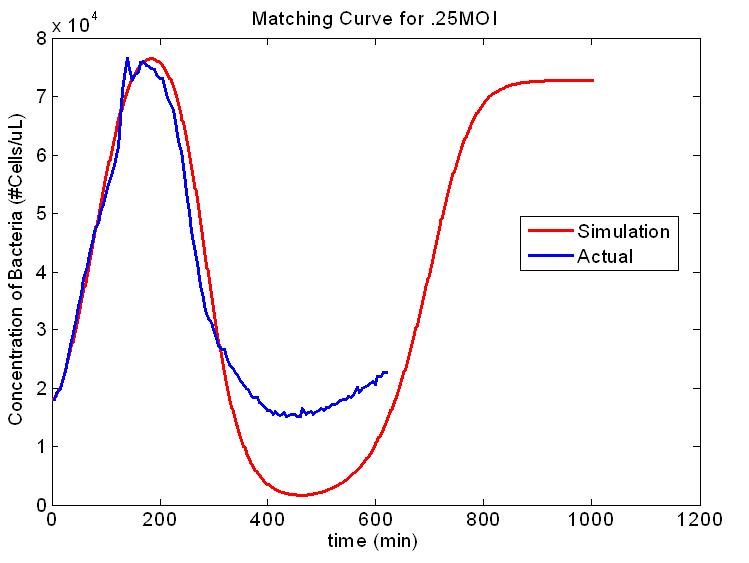

Figure 1. Second Scale of the Multi-scale Model. E. coli concentration vs. time for the infection with 1 virus per every 4 E. coli cells. The red curve is output from our model and the blue curve is experimental data. The model we built is multi-scale, specifically covering the growth of the host, and the spread of the phage within an isolated subpopulation. We also envisioned a third layer, the spread of the phage between artificially connected subpopulations. Integrating these levels of modeling to produce varying high-level population epidemic behavior by changing low-level parameters is one of the key aspects of our project. Building an understanding of high-level dynamics from the very lowest level of organization will allow us to more accurately predict the epidemiological outcome.

Testing the Model

Figure 2. The Reporter Plasmid at Work. A strain of E. coli carrying the reporter plasmid that has been infected with lambda phage. The red cell is lysogenic and the green cell is lytic. An important part of modeling is testing the model to see if it works in real life. To do this, we needed a model host and pathogen system. We decided to use Escherichia coli and Enterobacteria phage λ (lambda phage) since as a system they are well-studied and cheap and easy to work with. Lambda phage is also interesting because it can either immediately kill the host cell or it can insert its DNA and lie dormant. The decision to stay dormant (lysogeny) or to kill immediately (lysis) added a degree of flexibility to our model that allowed us to check the model robustness for slightly different phage. As part of the project we designed a reporter plasmid to generate florescent proteins and indicate the virus’ decision. This plasmid, along with the use of a phage modified to be florescent, we hoped, would allow us to determine how the population would act and verify our models.

|