BerkiGEM2007Present1

From 2007.igem.org

Heme

Introduction

Heme is a prosthetic group to hemoglobin. Generally, heme consists of an iron atom surrounded by a porphyrin ring. Each hemoglobin molecule is capable of binding up to four heme groups. One of the most important functions of heme is to assist in the transportation of diatomic gases. In red blood cells, heme and hemoglobin are the components that allow the binding of oxygen. As a result of this interaction, red blood cells continuously deliver oxygen to the entire body.

The Pathway

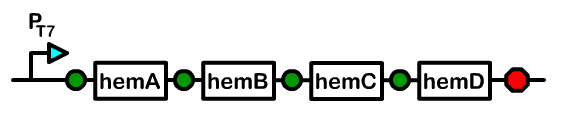

The biosynthetic pathway for heme demonstrates that there are eight enzymes, or heme genes, involved in the production of heme. Although bacteria already have these genes present in their genome, the amount of intermediates produced are insufficient for our purposes. We worked solely with hemA (Delta-aminolevulinate synthase), hemB (Delta-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase), hemC (porphobilinogen deaminase), and hemD (uroporphyrinogen III synthase) because over-accumulation of heme in our cells would result in toxicity. After successful subcloning experiments, the bacteria cell pellets would become reddish-brown due to the accumulation of porphyrins.

Design and Construction

First, we cloned hemA from R.capsulatus and hemA from CFT073, not knowing which hemA from which organism would give us the highest yield of heme. We also cloned hemB, hemC, and hemD from MG1655. Afterwards, we attached single ribosomal binding sites as well as library ribosomal binding sites. The advantage of working with library ribosomal binding sites is after transformation, one can grow single clones in a 96-well block and selectively choose the clone producing the greatest amount of heme, which correlates with the clone yielding the most red of pellets.

As depicted in the image to the left, because of the phenotype of porphyrins and heme, it was easy to select single colonies that combined with the strongest ribosomal binding sites of the library. These stronger clones would yield the greatest amount of heme and have the deepest red/brown color of all the clones.

After the ribosomal binding sites were attached to the heme genes, the genes were subcloned onto the same plasmid in sequential order. We placed the T7 promoter we produced at the beginning of the composite part as well as a terminator at the end.

Alternatives To Hemoglobin

Over the summer I investigated and created two alternatives to the hemoglobin part in our device. I worked with two genes we believed might allow our blood to carry more oxygen than hemoglobin.

The first gene I will discuss is H-NOX (Heme-Nitric oxide and Oxygen bonding). H-NOX is a heme-based sensor that is found in bacteria. H-NOX is able to bond to Oxygen using a distal pocket tyrosine. For this gene I added the T7 promoter we created for this project, an RBS site, and lastly a Bca1092 terminator. As I said previously this part would replace the hemoglobin part in our final device. When I assayed this part the results were inconclusive. The part was assembled correctly but the assay didn't show strong signs of expression.

The second gene I explored was Sperm Whale Myoglobin. Myoglobin is a monomeric protein that behaves as an intracellular oxygen storage site. Sperm whale myoglobin in particular is easily found in large amounts in the whale's muscle tissue. The construction of this part was very similar to that of the H-NOX composite part. Used the same promoter, terminator, and RBS. The assay for Myoglobin showed a bit more promise but couldn't conclusively show that Myoglobin was binding to oxygen.

With our construct complete, we employed UV-Vis to confirm that the red product we were seeing was, in fact, heme.