ETHZ/Engineering

From 2007.igem.org

.:: Introduction ::.

Having decided to work on an engineered biological system which exhibits learning, we elaborated on its design. Discussing with the biologists of the team, we realized that what we knew from the field of logic design as JK flip-flop with a latch may be implemented with biological parts using a modified toggle switch. Initial simulations showed us that it was possible to reach the desired behaviour. Therefore, a complete framework of differential equations describing the system was constructed and parameters were searched in the literature. Simulations performed with our new detailed model are very encouraging. In this page, the equations that model our system are and explained. The values that were chosen for the system parameters are presented and the results of our simulations are analyzed. References are provided at the end of the page. For an introduction to system modeling in synthetic biology, please read our modeling tutorial here.

.:: System Model ::.

Following the guidelines presented in our modeling guide, we divided the biological system into subsystems, each of which was modelled with a system of differential equations. According to what presented in the Biology Perspective, our system is composed the following three subsystems:

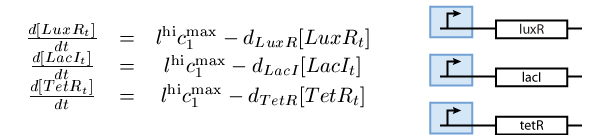

- A subsystem of constitutively produced proteins (see Fig. 1),

- The learning subsystem(see Fig. 2), and

- The reporting subsystem (see Fig. 3).

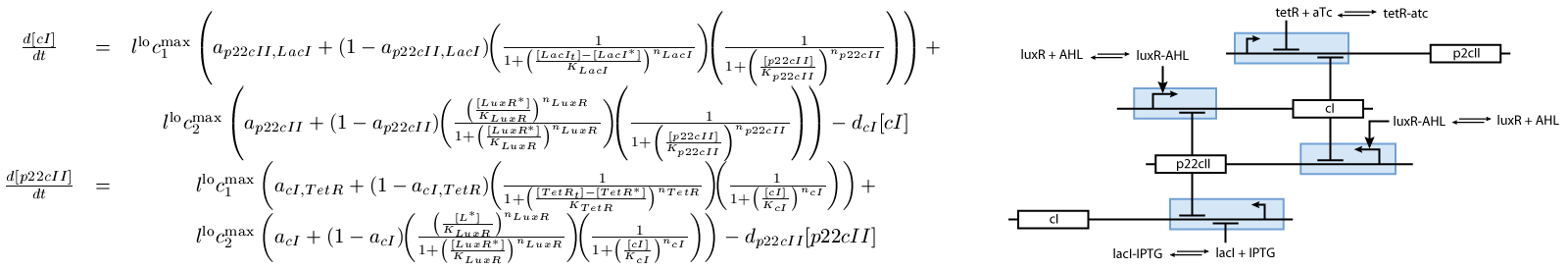

The second subsystem is the main part of our model. It stores the information concerning the learned information for the chemical of interest, and drives the production of the appropriate reporter during the recognition phase. It is actually a toggle switch that reaches its steady state depending on the chemical that it has been previously exposed to (see Fig. 2):

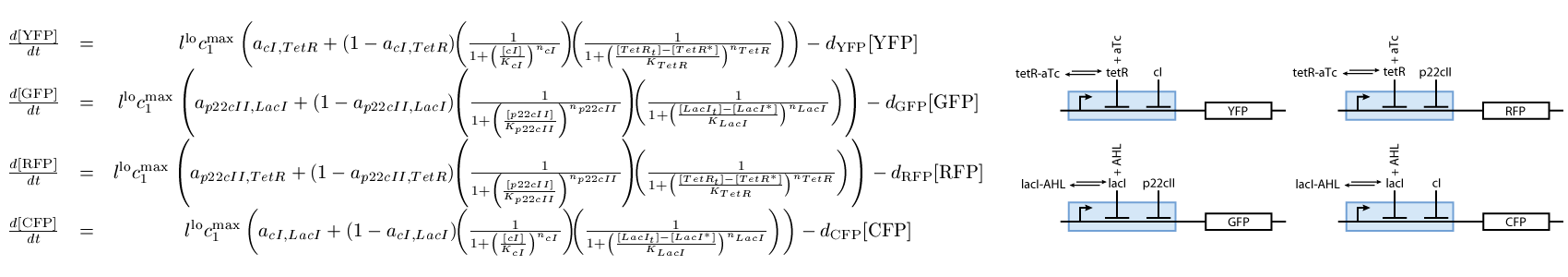

The third subsystem reports the state that our system is, during the different phases of learning and recognition. During the learning phase, this subsystem reports which chemical the cells are exposed to, and during the recognition phase, it reports if the cells recognize the chemicals that they are currently exposed to (see Fig. 3):

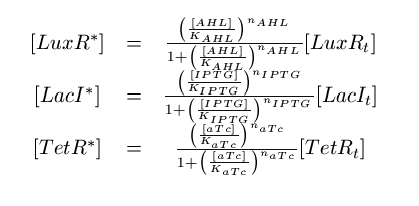

Note that the three constitutively produced proteins LacI, TetR and LuxR exist in two different forms; as free proteins and in complexes they build with IPTG, aTc and AHL, respectively. We need to model this complex-forming procedure, with another set of differential equations (Fig. 4):

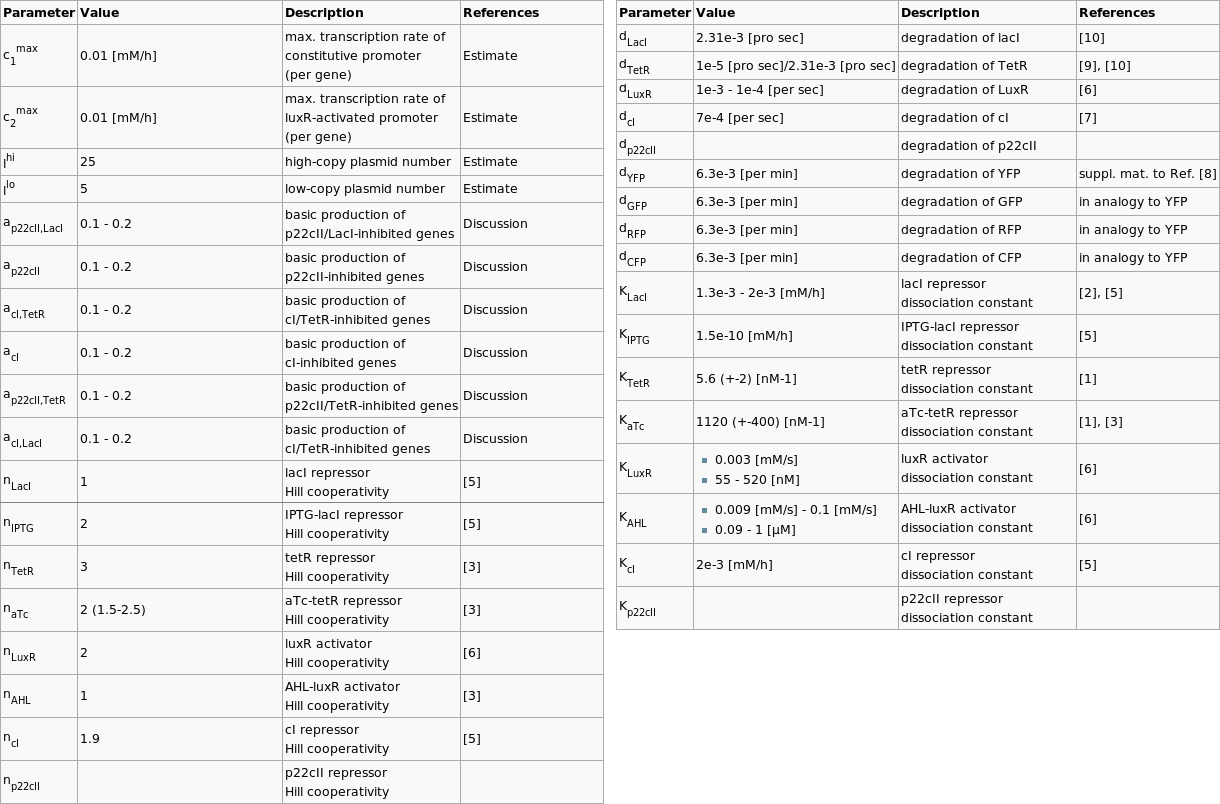

In order to have meaningful results from our simulations, we browsed through the literature in order to find appropriate values for our parameters. We reduced our parameter space by joining parameters together, and we gave reasonable estimates, for the values that could not be extracted from available publications. Since this is a hard part that every team has to face, we present the table with the chosen parameters below:

| Parameter | Value | Description | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| c1max | 0.01 [mM/h] | max. transcription rate of constitutive promoter (per gene) | Estimate |

| c2max | 0.01 [mM/h] | max. transcription rate of luxR-activated promoter (per gene) | Estimate |

| lhi | 25 | high-copy plasmid number | Estimate |

| llo | 5 | low-copy plasmid number | Estimate |

| ap22cII,LacI | 0.1 - 0.2 | basic production of p22cII/LacI-inhibited genes | Discussion |

| ap22cII | 0.1 - 0.2 | basic production of p22cII-inhibited genes | Discussion |

| acI,TetR | 0.1 - 0.2 | basic production of cI/TetR-inhibited genes | Discussion |

| acI | 0.1 - 0.2 | basic production of cI-inhibited genes | Discussion |

| ap22cII,TetR | 0.1 - 0.2 | basic production of p22cII/TetR-inhibited genes | Discussion |

| acI,LacI | 0.1 - 0.2 | basic production of cI/TetR-inhibited genes | Discussion |

| dLacI | 2.31e-3 [pro sec] | degradation of lacI | [10] |

| dTetR | 1e-5 [pro sec]/2.31e-3 [pro sec] | degradation of TetR | [9], [10] |

| dLuxR | 1e-3 - 1e-4 [per sec] | degradation of LuxR | [6] |

| dcI | 7e-4 [per sec] | degradation of cI | [7] |

| dp22cII | degradation of p22cII | ||

| dYFP | 6.3e-3 [per min] | degradation of YFP | suppl. mat. to Ref. [8] |

| dGFP | 6.3e-3 [per min] | degradation of GFP | in analogy to YFP |

| dRFP | 6.3e-3 [per min] | degradation of RFP | in analogy to YFP |

| dCFP | 6.3e-3 [per min] | degradation of CFP | in analogy to YFP |

| KLacI | 1.3e-3 - 2e-3 [mM/h] | lacI repressor dissociation constant | [2], [5] |

| KIPTG | 1.5e-10 [mM/h] | IPTG-lacI repressor dissociation constant | [5] |

| KTetR | 5.6 (+-2) [nM-1] | tetR repressor dissociation constant | [1] |

| KaTc | 1120 (+-400) [nM-1] | aTc-tetR repressor dissociation constant | [1], [3] |

| KLuxR |

| luxR activator dissociation constant | [6] |

| KAHL |

| AHL-luxR activator dissociation constant | [6] |

| KcI | 2e-3 [mM/h] | cI repressor dissociation constant | [5] |

| Kp22cII | p22cII repressor dissociation constant | ||

| nLacI | 1 | lacI repressor Hill cooperativity | [5] |

| nIPTG | 2 | IPTG-lacI repressor Hill cooperativity | [5] |

| nTetR | 3 | tetR repressor Hill cooperativity | [3] |

| naTc | 2 (1.5-2.5) | aTc-tetR repressor Hill cooperativity | [3] |

| nLuxR | 2 | luxR activator Hill cooperativity | [6] |

| nAHL | 1 | AHL-luxR activator Hill cooperativity | [3] |

| ncI | 1.9 | cI repressor Hill cooperativity | [5] |

| np22cII | p22cII repressor Hill cooperativity |

.:: Simulations ::.

.:: References ::.

[1] Weber W., Stelling J., Rimann M., Keller B., Daoud-El Baba M., Weber C.C., Aubel D., and Fussenegger M., "A synthetic time-delay circuit in mammalian cells and mice", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 104, no. 8, pp. 2643, 2007.

[2] Setty Y., Mayo AE, Surette MG, and Alon U., "Detailed map of a cis-regulatory input function", Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 100, no. 13, pp. 7702--7707, 2003.

[3] Braun D., Basu S., and Weiss R., "Parameter Estimation for Two Synthetic Gene Networks: A Case Study", IEEE Int'l Conf. Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing 2005, vol. 5, 2005.

[4] Fung E., Wong W.W., Suen J.K., Bulter T., Lee S., and Liao J.C., "A synthetic gene--metabolic oscillator", Nature, vol. 435, no. 7038, pp. 118--122, 2005, supplementary material.

[5] Iadevaia S., and Mantzaris N.V., "Genetic network driven control of PHBV copolymer composition", Journal of Biotechnology, vol. 122, no. 1, pp. 99--121, 2006.

[6] Goryachev AB, Toh DJ, and Lee T., "Systems analysis of a quorum sensing network: Design constraints imposed by the functional requirements, network topology and kinetic constants", Biosystems, vol. 83, no. 2-3, pp. 178--187, 2006.

[7] Arkin A., Ross J., and McAdams H.H., "Stochastic kinetic analysis of developmental pathway bifurcation in phage λ-Infected Escherichia coli cells", Genetics, vol. 149, no. 4, pp. 1633--1648, 1998.

[8] Colman-Lerner A., Chin T.E., and Brent R., "Yeast Cbk1 and Mob2 Activate Daughter-Specific Genetic Programs to Induce Asymmetric Cell Fates", Cell, vol. 107, no. 6, pp. 739--750, 2001.

[9] Becskei A., and Serrano L., "Engineering stability in gene networks by autoregulation", Nature, vol. 405, no.6786, pp.590--593, 2000.

[10] Tuttle L.M., Salis H., Tomshine J., and Kaznessis Y.N., "Model-Driven Designs of an Oscillating Gene Network", Biophysical Journal, vol. 89, no. 6, pp. 3873--3883, 2005.

.:: To Do ::.

- Christos: 1. Add gifs concerning the simulations

- Christos: 2. Remove the table with the parameters, once we have satisfying values.

- Katerina: 1. "The third subsystem has no feedback with the other two, as it is only used for producing the appropriate fluorescent proteins." Is this really true? gfp and rfp are situated in bigger parts with functionality. I think this needs to be rewritten more clearly.