Rice/Project A: Phage Project

From 2007.igem.org

Contents |

Phage Project

Background

Motivation

Bacteria are 'cleverer' than they seem at first glance! As humans dump antibiotic agents on these tiny disease causing microbes, they evolve strategies to evade these drugs. Since the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming, more potent drugs with the ability to neutralize a wider spectrum of microbes have been invented and used. As the disease treatment strategies harbor on use or more effective drug regimens, bacteria evolve their ability to evade death setting up an 'arms-race' between bacterial antibiotic resistance and application of multi-drug combinations used to combat resistance of the disease causing pathogen to the administration of a specific antibiotic.

Application of an antibiotic affects the adversity of growth environment of a bacteria. Following principles of population ecology, competition for common essential resources between two subsets of a genetically identical population, leads to application of selective pressure. Development of antibiotic resistance is a consequence of evolutionary adaptation by natural selection selecting for bacteria that are able to withstand the environmental pressure brought on by the antibiotic. Such resistance generally develops by one of the following ways:

1. Drug inactivation or modification: production of an enzyme that destroys the drug e.g. enzymatic deactivation of Penicillin G in some penicillin-resistant bacteria through the production of β-lactamases.

2. Alteration of structural target: e.g. beta lactams (alteration in penicilin binding proteins), quinolones (alteration in topoisomerases), amino-glycosides (alteration in ribosomal proteins).

3. Alteration of metabolic pathway: e.g. some sulfonamide-resistant bacteria do not require para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA), an important precursor for the synthesis of folic acid and nucleic acids in bacteria inhibited by sulfonamides. Instead, like mammalian cells, they turn to utilizing preformed folic acid.

4. Reduced drug accumulation :(a) by decreasing cell permeability to the drug by mutations in components in the cell wall or structure of porins, and/or (b) increasing active efflux of the drug from the cytoplasm by mutations in the efflux pump.

Development of multi-drug resistance comes about by either one or a combination of these mechanisms and is conferred by:

1. Development of mutational resistance: Mutations in genes affecting either or multiple of the 4 processes mentioned above.

2. Transfer or acquisition of resistance: Transfer from one bacteria to another.

Conventional strategies to counter the problem of multi-drug resistance include use of large amounts of more potent and multi-spectrum antibiotics, development of novel antibiotics targeting hitherto underutilized targets, and use of a combination of mutually antagonistic antibiotics. These methods tend to be expensive, harmful to the patient in the long run causing multiple side effects, and require a long time to implement.

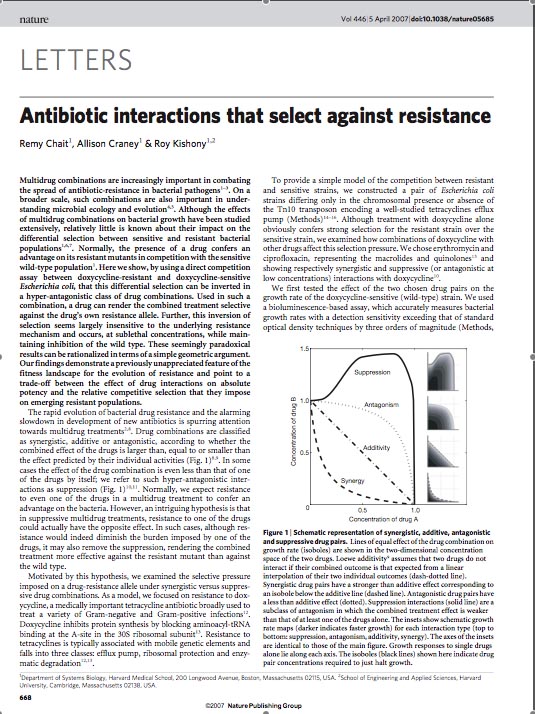

Roy Kishony's lab at Harvard played 'evolutionary competition games' on how differential selection between antibiotic resistance and sensitive bacterial populations is affected under a regime of multiple drug combinations. Normally, if two populations of the same bacterial strain compete, the one which mutated to acquire anti-biotic resistance 'wins' the fight for survival over the ones that remained wild-type and antibiotic sensitive. But, using a direct competition assay between Doxycycline resistant and Doxycycline sensitive E.Coli, under a particular regime of antagonistic antibiotic combinations, Chet et. al., demonstrate that the bacterial population harboring resistance is selected against in preference to the sensitive population. They find that in drug combination regimens that involve suppressive interactions (the combined effect of two drugs having less than a combined effect, which is also weaker than at least one of the drugs alone), high drug concentrations results in competitive selection against resistance, without perturbing the effectiveness of the other drug in the combination. These results are interpreted as coming from a trade-off regime in the evolution of resistance fitness landscape, where absolute potency of a drug combination is balanced by the relative competitive selection imposed on emerging resistant populations. Identification of reciprocally suppressive drug combinations in which each drug also impose selection pressures against the resistance developed to the other can be harnessed to counteract rapid development of multi-drug resistance.

Following up on this body of work, our iGEM team asked the following question: Can we artificially engineer a bacterial strain that would lead to utilization of the phenomenon of selection against antibiotic resistance in a bacterial population? In other words, given that the existence of 'selection against antibiotic resistance' in specific regimes of the evolutionary fitness landscape of a bacterial population, can we reverse engineer a system to recapitulate that specific fitness regime?

Goals

By conferring selective advantage on bacterial population, we intend to artificially create changes in evolutionary fitness landscape such that bacteria harboring antibiotic resistance are competed out. Towards this, we will take advantage of the following:

1. Antibiotic as a signaling molecule

2. Differential signals to resistant and sensitive bacteria

3. 'Immunity' of bacterial strain to lambda phage infection

4. Correlate sensitivity to antibiotic concentration with lysis versus lysogeny decision in phage infected bacteria.

Experimental System and Circuit Design

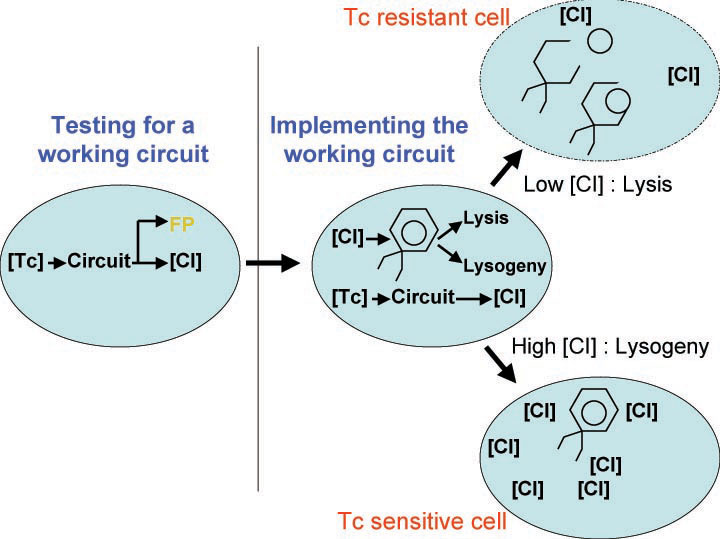

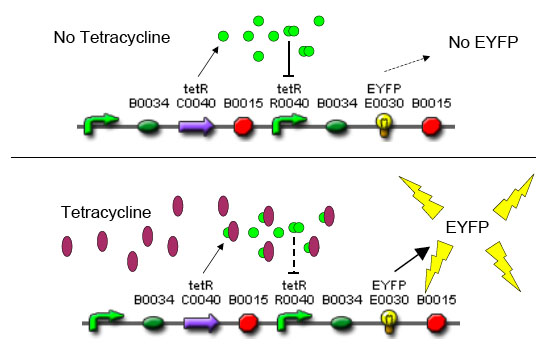

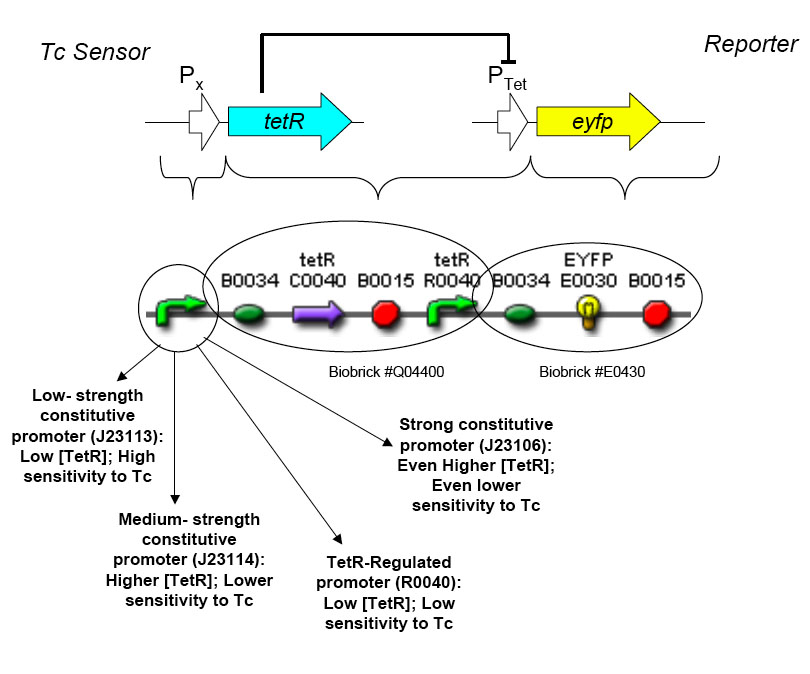

In order to set the stage for playing evolutionary competition games, we first engineer a bacterial population consisting of E.Coli cells that are either sensitive or resistant to the application of the antibiotic tetracycline. Our goal is to make cells harboring tetracycline sensitivity more fit than cells with tetracycline resistance. Ability to survive increasing concentration of tetracycline is used as a measure of fitness. The idea is summarized in the figures A and B:

MIC: the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial that will inhibit the visible growth of a microorganism after overnight incubation. Minimum inhibitory concentrations are important in laboratory culture conditions to confirm resistance of microorganisms to an antimicrobial agent and to monitor the activity of new antimicrobial agents.

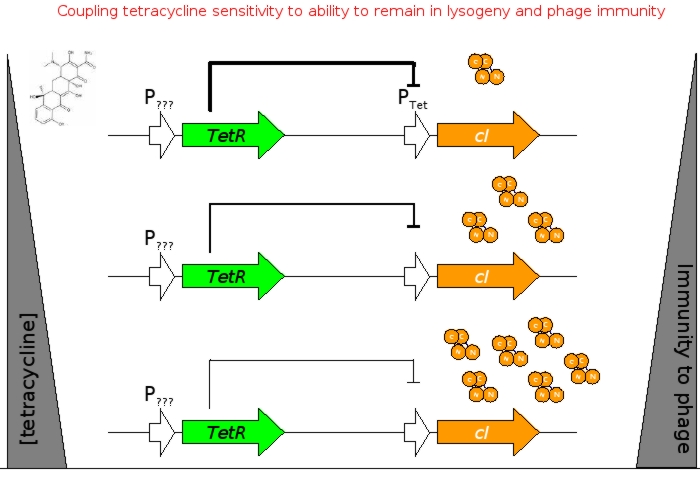

A bacterial cell infected with Bacteriophage lambda regulates the lysis versus lysogeny choice by modulating the amount of lambda repressor produced. High lambda repressor downregulates phage genes concurrently upregulating genes that allow it to remain in lysogeny. However, the lysis pathway switch is flipped upon decrease of lambda repressor brought about by induction by exposure to UV causing increase Cro protein. It follows that increased immunity to lambda can be induced by increasing concentration of lambda repressor, allowing the bacteria to remain in lysogeny. We simultaneously couple the lytic-lysogeny switch to tetracycline induced transcription of lambda repressor within one bacterial cell as well as tetracycline induced antibiotic resistance to comparison of fitness between resistant and sensitive cells, in order to characterize the proof of principle of selection against resistance. By this coupling, we want to tune the parameters in our system such that we land in the fitness regime that will confer selective advantage to the cells with Tetracycline sensitivity, simultaneously lowering the lethality of cells with Tetracycline resistance. The idea is summarized in the figure below:

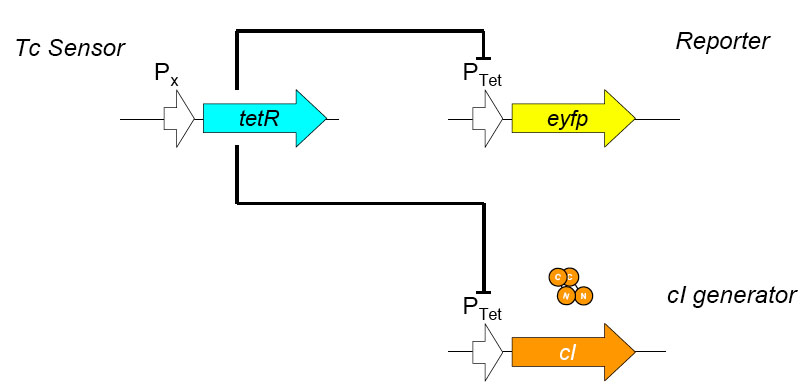

Basic Circuit Design - The general strategy for linking lysis to tetracycline resistance, involves putting a lambda transcription factor (CI) under control of the Tet promoter. This circuit makes the amount of CI in a cell proportional to the amount of tetracycline in the cell. Cells with higher concentrations of tetracycline have higher levels of CI thus preventing lysis of the cell via phage. Cells with lower levels of tetracycline (cells that are resistant to tetracycline) will have less CI present and thus be more likely to be lysed by phage.

We designed the circuit keeping in mind the following attributes:

- a circuit with existing BioBricks requiring few ligations to construct

- a design that could be used with multiple types of resistance

- a robust circuit that will remain stable for large numbers of generations

- a circuit that can propagate through bacterial populations, e.g., practical for treating environmental problems

Antibiotic Selection - The antibiotic resistance we will be selecting against in this circuit will be tetracycline. Tetracycline was selected because Tn10 tetracycline resistance transposon has been extremely well characterized and can be activated by a non antibiotic molecule anhydrotetracycline that binds to the TetR transcription factor, allowing us to use a variety of approaches when characterizing the genetic circuit. Also, the human body is extremely tolerant of tetracycline, making it a good target for resistance reduction.

Strain Selection – To compare the relative fitness of tetracycline resistant versus that of tetracycline sensitive phage infected cells, we selected two strains of E.coli genotypically identical with the exception that one has the Tn10 tetracyline resistance transposon. These nearly identical strains will allow us to asses the impact of tetracycline resistance on relative fitness.

Bacteriophage Selection - When selecting the bacteriophage to be used in this circuit, we desired a phage whose life cycle and genome had been well characterized. Bacteriophage lambda has all of these characteristics as well as the benefit of being commonly used as a cloning vector. Specifically, the lambda strain we selected can be induced to undergo lytic growth by growing lysogenic cells at 42°C. Also, due to the infectious nature of bacteriophage lambda, we selected a strain that is unable to lyse cells (amber mutation preventing the expression of lytic enzyme, protecting other bacteria within the lab from phage infection). Though the phage will not lyse the cells, it will produce fully functional phage particles that can be isolated via chloroform extraction.

Phage Engineering – We will construct a recombination plasmid designed to integrate our circuit into lambda DNA located chromosomally in lysogen E.coli. The plasmid will not contain an origin of replication (to limit recombination sites), so we will have to amplify it using high fidelity PCR. The plasmid will contain our circuit flanked by homologous recombination sites that will combine at non-critical location of the phage chromosome (yet to be determined) .

Circuit Characterization – To assay relative fitness of the cells, we will measure doubling times of the strains at sub-MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) tetracycline by measuring optical density (OD at 600nm) of cells.

Experimental Materials and Methods

The overall construction scheme with the modular parts of the circuit is mentioned in Figure C. Differential response to exposure to Tetracycline is schematized in Figure D. Biobricks parts used in the circuit is mentioned in Figure E.